Thursday, August 10, 2017

Calypso in Farid El Atrash's film, Mā Ta’ūlsh le Ḥad (1952)

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Another Jajouka movie

(And please see Schuyler's astute article, "Joujouka/Jajouka/Zahjoukah: Moroccan Music and Euro-American Imagination", which you can read here.)

There is Augusta Palmer's Hand of Fatima (2010).

And now there is another, Jajouka Quelque Chose De Bon Vient Vers Toi, by Eric and Marc Hurtado, members of the experimental/industrial music group Étant Donnés from Grenoble. The brothers were born in Rabat, Morocco. The film is entered in the 27th Marseille International Film Festival, to be held in July 2016. The festival website has this to say about the film:

The film opens with an archaic tale, in brief stylised tableaux, concerning the divine creation of music. The myth is extended to a universe of sacred dimensions where it is difficult to differentiate the legend from its current perpetuation. Where are we? In the Moroccan Rif, in Jajouka, a village where, for over two thousand years, fertility rites involving music and dance, have been presided over by Bou-Jeloud, “the Father of Skins”, a local version of the god Pan.

The Hurtado brothers are famous musicians: their group Etant Donnés came to prominence through collaborations with various artists including Alan Vega, Genesis P-Orridge and Philippe Grandrieux (they produced original soundtracks for several of his films). They are also known as experimental filmmakers. Here their two passions are combined, raising the challenge of travelling back in time to hail the Master Musicians of Jajouka, yesterday and today. Besides, has time passed? It is therefore not about concocting a score destined to accompany autonomous images, but about making the music (its strident nudity, its incantatory austerity) and its history the very substance of the images and the scenario being staged. Their choice was obviously Pasolinian: to resurrect the archaic while remaining faithful to it, through the treatment of decor, lighting, acting and costumes. Here, the beauty lies in the rough friction between the muteness of the characters and their unbridled momentum towards another potential voice.

Thursday, January 07, 2016

Listen to Radiooooo...and Ahmed Malek

There is much more to explore, but I, typically, went to Algeria, 1970s, and came up with a track by Ahmed Malek, called "Autopsie d'un complot." Check it out:

Monday, December 08, 2014

Coming soon: Gil Hochberg, "Visual Occupations: Violence and Visibility in a Conflict Zone"

"Focusing on the politics of visuality, Visual Occupations engages the Zionist narrative in its various scopic manifestations, while also offering close readings of a wide range of contemporary artistic representations of a conflictual zone. Through such key notions as concealment, surveillance, and witnessing, the book insightfully examines the uneven access to visual rights that divides Israelis and Palestinians. Throughout, Gil Z. Hochberg sharply accentuates the tensions between visibility and invisibility within a context of ongoing war and violence. Visual Occupations makes a vital and informed contribution to the growing field of Israel/Palestine visual culture studies."

and mine:

"Gil Z. Hochberg's brilliant and lucidly written text provides a vivid analysis of the sharp limits on visibility in Palestine/Israel. The expulsions of Palestinians in 1948 are invisible in Israel, and yet they continue to haunt its citizens and mobilize Palestinian resistance. Palestinians under occupation are hyper-visible, as victims and militants, and they seek both non-spectacular images and a measure of opacity. Through her critical readings of an array of Palestinian and Israeli artistic works, Hochberg offers other ways of looking and being seen, in this vastly unequal field of visibility."

and Duke Press' description:

"In Visual Occupations Gil Z. Hochberg shows how the Israeli Occupation of Palestine is driven by the unequal access to visual rights, or the right to control what can be seen, how, and from which position. Israel maintains this unequal balance by erasing the history and denying the existence of Palestinians, and by carefully concealing its own militarization. Israeli surveillance of Palestinians, combined with the militarized gaze of Israeli soldiers at places like roadside checkpoints, also serve as tools of dominance. Hochberg analyzes various works by Palestinian and Israeli artists, among them Elia Suleiman, Rula Halawani, Sharif Waked, Ari Folman, and Larry Abramson, whose films, art, and photography challenge the inequity of visual rights by altering, queering, and manipulating dominant modes of representing the conflict. These artists' creation of new ways of seeing—such as the refusal of Palestinian filmmakers and photographers to show Palestinian suffering, or the Israeli artists' exposure of state manipulated Israeli blindness—offers a crucial gateway, Hochberg suggests, for overcoming and undoing Israel's militarized dominance and political oppression of Palestinians."

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

a mesmerising film about Damascus

a four-minute short that merely shows a slice of life in the city. It captures people walking, façades of old buildings, iron doors, shadows of trees, clouds kissing steeples, city lights and calligraphy carved into walls. Filmmaker Waref Abu Quba’s style captures the aesthetics of nostalgia itself due to the way in which images filter and flit across the screen – languorous, soft, full of flux and a kind of bittersweet joy. It is a particularly touching reminder of a city that, due to the ongoing war, has become lost to the world as a place of vibrant vitality, beauty, history and quite simply, humanity. This choreography of images is set to the sound of legendary Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s poem, “The Damascene Collar of the Dove” -- from here. and there's more.

the stranger sleeps

on his shadow standing

like a minaret in eternity’s bed

not longing for a land

or anyone . . .

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

More on 'Traitors': #women #punk #Morocco

1. An article about the film's star, Chaimae Ben Acha, in Brownbook.

Chaimae plays Malika, leader of an all-girl punk band in Tangier (she's in white in the photo below).

Ben Acha’s preparation for the role required her to cut her hair like Joan Jett, enrol in singing lessons and wear combat boots while off-set so as to acquire a rebellious strut. She admits that prior to the filming of ‘Traitors’, she had ‘nothing to do’ with rock music. ‘To sing rock ’n’ roll, you have to be hard-edged. It’s not feminine,’ she says.

2. And, another preview. Music sounds great. Can't wait to see it.

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Another Palestinasjal (Swedish for Palestinian Kufiya) in the Sunday New York Times

It's the same film as before, Lukas Moodysson's We Are the Best!, about three Swedish girls who start a punk band in the early 80s. I spotted this, along with Marc Spitz's review, in the print edition of the New York Times on Sunday, May 28, 2014. It sounds like a great film.

And I will tell you once again: in Sweden they simply call the kufiya a Palestinasjal or Palestinian scarf. The film is based on a graphic novel by the filmmaker's wife Coco Moodysson's, which recounts her experiences as a young punk in the early 80s. Kufiyas were there, as they were in the US.

Friday, March 21, 2014

The film "Traitors": women, punk, Morocco

Traitors (dir. Sean Gullette) has been on the festival circuit for a couple years. It looks, based on the reviews and the available trailers, to be a good one. I was alerted to it by Joobin Bekhrad's review in REORIENT, which also features one of the trailers. The latter features the lead, Malika, and her all-female Moroccan punk band doing a version of The Clash's "I'm So Bored with the USA," in Arabic, but with the chorus, "I'm so bored with Mo-ro-cco" sung in English.

Among other things, Bekhrad writes, "Gullette’s film appears to be one centred around the power and allure of rock music, particularly in a North African context; however, as it progresses, it also comes to provide a powerful social commentary on the current generation of Morocco’s youth and their hopes, aspirations, frustrations, dilemmas, and anxieties, evoking at times a mood similar to that prevalent in earlier films such as Fatih Akin’s Head On..." If it's anything like Head On I it should be worth watching. We can only hope.

(I liked Bekhrad's review but it was marred by a move that everyone writing in English about Middle Eastern pop music seems to make, which is "clever" puns. A couple examples: "stuck between Maroc and a hard place" and "Maroc and roll, baby." Er, enough.)

Here's another clip from the film:

And some more info:

"Features original songs sung by its riveting star Chaimae Ben Acha [who plays Malika, the leader of a Tangier punk band], and new music from much-hyped all-female bands Savages and Talk Normal." (I've not been able to find any of their music, however.)

Here's an interview with the director, published in Variety. Where we learn, among other things, that the film was funded with a grant from the Sharjah Art Foundation.

And, a review in The Hollywood Reporter, quite positive.

Friday, December 06, 2013

Kufiyaspotting: Psychosis 2010

Friday, January 04, 2013

dangerous turbans: Iqbal Singh

Iqbal Singh does Elvis. "A Beautiful Baby of Broadway," from the 1960 Hindi film, Ek Phool Char Kaante.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

Director Alison Klayman: Kufiya Dress

From today's New York Times (July 22, 2012), a review of first-time director Alison Klayman's documentary about Chinese avant-garde artist Ai Weiwei, and showing Klayman wearing: a kufiya dress. (Klayman is a Brown graduate; perhaps she picked up her fashion sense there.)

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Rachel Leah Jones' "Targeted Citizen"

Targeted Citizen - English from Adalah on Vimeo.

You really must see this film from Rachel Leah Jones and Adalah-The Legal Center for Minority Rights in Israel. In 15 minutes, it systematically exposes the manifold ways in which the Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel (20% of its population) are discriminated against by the self-proclaimed Jewish state. 20% of the population that owns only 2.5% of the land. Particular difficulty is faced by the 60,000 Arab Palestinians who live in "unrecognized villages." Director and producer Rachel Leah Jones has made a brilliant film about one such "unrecognized village," Ayn Hawd Jadida, which is called 500 Dunam on the Moon.Monday, December 28, 2009

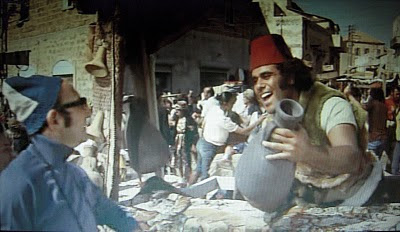

Tarbushes and kufiyas (but no Arabs) in "Kazablan"

In this scene, the Mizrahi character, at left, smoking nargila, is exchanging insults with Yanush, the Ashkenazi character at right, the owner of a shoe store, who is presented in an entirely unsympathetic light. (The latter is Kazablan's rival in the quest for the hand of the Ashkenazi girl Rachel.)

The exoticness of the Mizrahim of Kazablan is also established by the neighborhood in which they live--one which is crumbling, and threatened with demolition by the municipality. It is in fact a "mixed" neighborhood of Ashkenazim and Mizrahim--not in fact very sociologically accurate--but it is the Mizrahim who seem to define its character, who seem to "belong" in a way that poorer Jews from Eastern Europe appear not to. Of course the neighborhood is old Jaffa, the historic Arab-Palestinian city just to the south of Tel Aviv, denuded of most (but not all) of its Arab inhabitants in 1948. Nowhere in the film, I'm pretty sure, is the name Jaffa (Yaffa, in Arabic), mentioned. Here's a shot of the open-air market, from above. Note the rubble (Mizrahim are of the slums), note the primitive atmosphere lent by the horse drawn carriages, near the beach, and at the bottom, at the left and the right. Note that the stone structures clearly signify "Eastern." They are typical of Arab structures throughout in cities throughout the Mediterranean from the first half of the twentieth century. As a resident of Beirut from 1964-1976, they are entirely familiar to me.

Here's another view. The impressive structure on the right, with its red-tiled roof, is entirely typical of Arab cities like Jaffa, Haifa, Beirut...

At the same time, while the architecture suggests Arabness, in the film, it is not allowed to say it. One of the most fascinating ways in which the Arabness of the Mizrahi characters is erased in the film is through the music. The film is a musical, full of staged scenes that appear (to me) rather silly and ridiculous. But what is particularly remarkable is the fact that the music is the typical popular Israeli music of the era, rooted in Eastern-European styles, with only a hint or two of Easternness. It reflects hegemonic ideas about the nature of national music, but it has almost nothing to do with the reality of what Mizrahim were into at the time. Their music was rooted in the East, in the Arab world, and the broader Mediterranean. This was a dynamic time for the development of what is variously known as Israeli Mediterranean Music or Mizrahi Music. In the film, however, the Arab musical traditions that were popular in real Mizrahi neighborhoods is nowhere present. The only time it is suggested is in the nightclub that Kazablan and his pals frequent, where Greek music (acceptable because it's "Eastern" and exotic without being Arab) is performed.

I know virtually no Hebrew, but it also struck me that the Hebrew spoken by the Mizrahi characters was sprinkled with less Arabic than I would have expected.

The Arabness of Jaffa, and of Israel more generally, nonetheless haunts the movie. For instance, this scene, where Kazablan and his pals are prancing around, singing a song. In the background is Jaffa, where a minaret and church steeple are visible, signs of a former presence of a now mostly vanished Arab community, that add to the picturesque atmosphere of the scene. (Kazablan is in the center, dressed in denim, with the fisherman's cap.)

At the same time, while the architecture suggests Arabness, in the film, it is not allowed to say it. One of the most fascinating ways in which the Arabness of the Mizrahi characters is erased in the film is through the music. The film is a musical, full of staged scenes that appear (to me) rather silly and ridiculous. But what is particularly remarkable is the fact that the music is the typical popular Israeli music of the era, rooted in Eastern-European styles, with only a hint or two of Easternness. It reflects hegemonic ideas about the nature of national music, but it has almost nothing to do with the reality of what Mizrahim were into at the time. Their music was rooted in the East, in the Arab world, and the broader Mediterranean. This was a dynamic time for the development of what is variously known as Israeli Mediterranean Music or Mizrahi Music. In the film, however, the Arab musical traditions that were popular in real Mizrahi neighborhoods is nowhere present. The only time it is suggested is in the nightclub that Kazablan and his pals frequent, where Greek music (acceptable because it's "Eastern" and exotic without being Arab) is performed.

I know virtually no Hebrew, but it also struck me that the Hebrew spoken by the Mizrahi characters was sprinkled with less Arabic than I would have expected.

The Arabness of Jaffa, and of Israel more generally, nonetheless haunts the movie. For instance, this scene, where Kazablan and his pals are prancing around, singing a song. In the background is Jaffa, where a minaret and church steeple are visible, signs of a former presence of a now mostly vanished Arab community, that add to the picturesque atmosphere of the scene. (Kazablan is in the center, dressed in denim, with the fisherman's cap.)

Now we come to the kufiya scenes. The first occurs in the course of one of Kazablan's most well-known songs, "Kulanu Yahudim" (We Are All Jews), which sums up the ideological point of this, and all other bourekas films: despite the differences between Jews of European and Eastern background, all are ultimately united as Jews, and as Israelis, in a common purpose, in the Jewish state. (You can watch the scene here. The quality is poor, but you will get the idea. And also a flavor of the music that characterizes the film.) What is amusing is that if you watch closely, a male figure in a kufiya (and 'iqal, the headband) appears at one point, dancing with a blonde, presumably Ashkenazi, Jewish woman. (Bottom right.) What are we to make of this? It would appear to signify that even Arabs in the Jewish state are "all Jews." Or is this some kind of joke on the part of the director. Whatever the case, the Palestinian Arab, citizen of Israel, certainly haunts the scene.

A kufiya shows up at one other point. Rachel, the love interest of Kazablan and Yanush, is walking through the neighborhood market. If I'm not mistaken, pondering who to choose. For just a moment, just behind Rachel, we spot another person wearing a kufiya--this time, black-and-white. He is probably present so as to mark the neighborhood, once again, as exotic and colorful. But he is not offered any opportunity to assert his Arabness. Nonetheless, he, and his kufiya, is a mark of the specter that cannot, will not, be eliminated.

Sunday, March 08, 2009

Recommended reading on "Waltz with Bashir" and the other (Sudanese) Bashir

There is a final irony. Waltz with Bashir holds a redemptive message, celebrating the necessity and the ability to confront one’s past. Yet the film and its reception exemplify the strictly enforced boundaries of any debate on Israel’s past and present transgressions.

Also from Middle East Report Online, Khalid Mustafa Medani's analysis of the ICC's indictment of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir.

By Bashir’s calculation, the ICC decision is not the end of the road. His primary objective is to consolidate the junta’s power by expanding oil production in Darfur and elsewhere. Only a genuinely democratic transition stands in the way of this objective. The ICC’s warrant for Bashir’s arrest will have little effect in resolving the larger problem in Sudan: the lack of participatory politics. Only if this warrant is followed by a concerted effort to support free and fair elections will it fulfill its promise.

Sunday, August 31, 2008

Against Sixties Nostalgia: "Easy Rider"

From an article in today's New York Times Arts & Leisure section, about the 60s independent films of Robert Downey--which I had not heard of, nor have I seen. Since they've now been restored, I'll hopefully have a chance.

I was pleased to see the jab at Easy Rider. I've wanted to write something about some of the problems I see with iconic films of the sixties, which were much admired at the time, and which I must admit, I too liked a lot when they first came out. (Thanks to AMC, I've had the opportunity to see many of them again, for the first time since the sixties.) Easy Rider celebrates male hippy pot-smoking freeliving renegade motorcycle riders, turning them into martyrs at the hands of Southerners. That is, long-haired virtue is produced at the expense of a stereotype of redneck evil. (There is also an implicit identification made between the victimhood of the white hippies and that of African Americans, who suffered at the hands of crackers during the civil rights struggles.) I remember coming out the of theater after watchin g Easy Rider in summer 1969, feeling shocked and outraged. I didn't ride a motorcycle, but I did have the long hair. So I certainly identified with the Fonda, Hopper and Nicholson characters. It worked with me.

I was pleased to see the jab at Easy Rider. I've wanted to write something about some of the problems I see with iconic films of the sixties, which were much admired at the time, and which I must admit, I too liked a lot when they first came out. (Thanks to AMC, I've had the opportunity to see many of them again, for the first time since the sixties.) Easy Rider celebrates male hippy pot-smoking freeliving renegade motorcycle riders, turning them into martyrs at the hands of Southerners. That is, long-haired virtue is produced at the expense of a stereotype of redneck evil. (There is also an implicit identification made between the victimhood of the white hippies and that of African Americans, who suffered at the hands of crackers during the civil rights struggles.) I remember coming out the of theater after watchin g Easy Rider in summer 1969, feeling shocked and outraged. I didn't ride a motorcycle, but I did have the long hair. So I certainly identified with the Fonda, Hopper and Nicholson characters. It worked with me.Such infantile and ill-informed sorts of representations (echoed in many other cultural artifacts of the time, like Neil Young's "Southern Man" and the film Deliverance) have had pernicious political effects, and are a part of the complicated story of how the South has gone very Republican. I've lived in Texas and Arkansas for a total of over twenty years, and I still have friends from the coasts, and urban centers in the Midwest, who can't understand how anyone could possibly live in the South or how anything good could possibly come out of (t)here. They are still apprehending the South through the lens of Deliverance and Easy Rider, it seems.

Other films I've been meaning to write brief notes about are MASH and its homophobia and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and its sexism. I was completely blind to these issues when I originally saw these films. And I considered myself a political radical. I guess I'm trying to make sense of my own memories of the sixties.

So I vote for a revival of "Chafed Elbows." And "Flaming Creatures"!

More in future, I hope...

Sunday, July 27, 2008

R.I.P. Youssef ("Jo") Chahine

Allah yarhamu.

Egypt's great filmmaker, Youssef Chahine, passed away this morning in Cairo, at the age of 82. I was no great fan of most of the films he produced over the past two decades, but his production of the fifties and sixties puts him in the class of one of the world's great filmmakers. Cairo Station (Bab al-Hadid) in particular is quite simply, an almost perfect film. (See my earlier, brief, comments on it here.)

The photo shows Chahine in his role as Qinawi, in Cairo Station, holding a knife to Hanuma (played by Hind Rustum).

Note that the AFP story on Chahine's death linked to above includes a statement by French President Nicolas Sarkozy praising the director. In France, even a right-wing politician who is elected on an anti-immigrant platform is expected to have something favorable to say about an Arab artist with a global reputation. There would be no such expectation of Obama, if he is elected president, especially when it comes to Arab artists. Unless they have been approved as "moderate," i.e., in favor of peace with (read: surrender to) Israel. Which means no Nobel prizes, or favorable statements, about any for Arab artists, post-Naguib Mahfouz (d. 2006). Chahine was not "moderate."

Check out this smart obit in The Guardian. As of this moment, the New York Times has not seen fit to mention his death.

Saturday, July 21, 2007

"Performance" and Hassan i-Sabbah

I recently watched Performance (1970) again. I first saw it when I lived in Beirut, shortly after it was released. Given the fact that there are lots of shots of bare breasts, which were of course cut by the Lebanese censor, it's amazing that the film was so coherent the first time I saw it. What I had remembered about it was (1) that the gender-bending, both of the reclusive rock star Turner (Mick Jagger) and gangster-on-the-run Chas (James Fox) was quite mind-blowing, (2) the soundtrack was fabulous, especially Ry Cooder's slide guitar, and (3) Jagger's song, "Message from Turner," was terrific as well. These impressions all held up on second viewing, although it appears that not all the slide guitar playing is by Ry Cooder, because Lowell George (of Little Feat fame) plays guitar on the soundtrack as well.

What I didn't remember, and probably did not appreciate at the time, was what one might call the Burroughsian Orientalist themes and atmosphere. First Turner's house, where Chas takes refuge, bears a strong resemblance to a harem--the decor, the fact that Turner lives with two women (Pherber, played by Anita Pallenberg, and Lucy, played by Michèle Breton), the robes worn by Pherber and Lucy, and the decadence. Except that Jagger, with his long hair, androgynous looks and dress, and lipstick, often as much like one of the women of the harem than its master. And if purdah is imposed, it's self-imposed upon the reclusive Turner as it is upon Pherber and Lucy.

And then there is the scene where Jagger is reading from a book about the "Legend of the Assassins" (I'm not sure what the source is) and he quotes the famous lines of Hassan i-Sabbah (which by now have begun to seem a little trite from overuse): "Nothing is forbidden, everything is permitted." Hassan i-Sabbah (1034-1124), the celebrated/infamous leader of the Nizari Ismailis, was an important figure in the novels of William Burroughs. (The best analysis of Burroughs' use of Hassan i-Sabbah is to be found in Timothy Murphy's Wising Up the Marks.) Burroughs' pal and collaborator Brion Gysin was very much into Hassan i-Sabbah as well, and perhaps he's responsible for the "Assassin" leader's appearance in the film? After all, Gysin did lead Brian Jones to Jajouka in 1968, where he recorded the tracks that would eventually would appear (with effects added by Jones) as Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Jajouka in 1971.

If I'm not mistaken, the last shot in the movie is of Hassan i-Sabbah's fortress at Alamut, in northern Iran. The soundtrack also includes some Persian touches, as the Iranian santur player Nasser Rastegar-Nejad appears in the mix.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

“Rockers, Feminists and Homosexuals: Diversionary Scenes in Chahine’s 'Bab al-Hadid'”

I attended the Middle East Studies Association meetings, November 18-21, in Boston, where I presented a paper on Youssef Chahine's classic 1958 film Cairo Station (Bab al-Hadid). The entire panel was devoted to the film, and also featured papers by my UA History Department colleague Joel Gordon and by Elliott Colla (Comp Lit, Brown). It was a great panel, an all-too-rare occasion to focus attention on a single work. I offer below the opening paragraph of the paper; if anyone is interested in the whole thing, they can write me.

I propose today to concentrate our attention away from Bab al-Hadid’s main plotline, the gradual descent of Qinawi into madness and attempted homicide, and toward on three scenes which, according to conventional analyses of the film, serve as entertaining “distractions” from the story’s forward momentum. Film critic Viola Shafik, for instance, describes such scenes, of which there are several, as “inserts” that function as “observations made by Qinawi” and “allow the audience to participate in his voyeurism” (2001: 78). Shafik claims as well that Bab al-Hadid represents a “successful mélange of social criticism and entertainment” (Ibid). Her assertion that these scenes are Qinawi’s observations, however, is problematic because he is not always present, and where he is, the scene is often not shot from his point of view. In addition, Shafik trivializes such scenes by naming them as “inserts” and posing them as “entertainment” in contrast to the ostensibly more serious scenes of “social criticism.” My analysis by contrast foregrounds such scenes and suggests that the film’s pleasures derive as much from the “inserts,” the excesses, as they do from the unfolding tension of the main plot. Rather than viewing them as “mere” entertainment, I want to argue that they both reflect as well as comment on Egypt’s social conditions in significant ways. In addition, attention to such scenes can help us to deepen our appreciation of depicted in Bab al-Hadid as a sight of remarkable social dynamics and interactions, as a crossroads, as the narrator Madbouli states at the film’s opening, where a very heterogeneous variety of social classes and types interact: “northerners and southerners (bahri wa ‘ibli), foreigners and locals, the rich and poor, the employed and those out of work.” These include encounters between travelers of all sorts and the relatively fixed population of workers like Qinawi the newspaper peddler (Youssef Chahine), Hanuma the soda pop vendor (Hind Rustum), and Abu Siri‘ the porter (Farid Shauqi), who provide services to those coming and going, but who are also, in a sense, travelers themselves, as part of Cairo’s burgeoning population of rural-to-urban migrants (Gauthier 1985: 57).

I proceeded to examine three scenes that I call the rock ‘n’ roll, the feminist, and the gay pickup scenes.

The photo shows Hanuma (played by Hind Rustum) on the train with the rock 'n' rollers.

Tags: film, Egypt, Youssef Chahine