There have been few posts on this blog of late in part because I'm trying to focus on the manuscript for my book,

Radio Interzone. Lately I've been working on the chapter on rai music, to be based in part on articles published previously, some with Joan Gross and David McMurray others on my own. (See the bibliography at the end.) Lately I've been reading or rereading a number of articles on rai, both journalistic and academic, gathered over the last three years or so. In the course of doing so I've noticed a number of myths and misconceptions, that keep being repeated, over and over, in the literature. I attempt to correct the record here, as best I can. Or maybe I should say, I attempt to problematize the truisms that circulate, endlessly, about rai. Some of what I write re-states what I/we have written before. (And I must admit, I/we are responsible for circulating some of the errors.)

1. Rai means “opinion” in Arabic. From this claim flows an understanding that the lyrics of rai convey the opinion of the singer, in a fairly straightforward and unmediated way. Such “opinion,” moreover, is for the most part, direct, and, by implication, oppositional.

Rai of course literally means “opinion” or point of view. But in this musical genre, the significance of the word is not so much its literal meaning but that it functions, in many songs, as a word or phrase like “oh yeah,” “yeah, yeah,” or “tell it like it is.” That is, it serves to emphasize whatever point is being made. (see Mazouzi, 269)

Siclier Sylvain, writing in

Le Monde, makes the related claim that rai expresses singers' ideas directly, rather than metaphorically: “Issu des expressions musicales populaires, preferant les mots directs à la metaphore pour se libérer des tabous...”

Sylvain's assertion demonstrates that anyone picks up the pen to write about rai should first be required to read the Danish ethnographer Marc Schade-Poulsen's

Men and Popular Music in Algeria: The Social Significance of Raï, which is based on fieldwork he did in Oran, the city where rai originated, right before the outbreak of the Algerian civil war in 1992. In chapter five (“Listening to Rai”) Schade-Poulsen discusses his attempts to determine what sort of meanings his young informants made of a few important rai songs. It turns out that the songs in question (and they are pretty typical) are highly metaphorical and that his informants attribute a range of opinions as to what the lyrics “mean.” In some cases, the songs are based on traditional texts (the deep sources of rai songs are rural, and especially Bedouin), and so his informants could only guess what the songs were about, and did not understand some of the words. Interpretations, due to the metaphorical nature of the lyrics, varied widely.

So much for rai as “

mots directs.”

Furthermore, Schade-Poulsen explains that unlike rock'n'roll as it developed in the West in the sixties, and to which rai is typically compared, rai music lyrics are not “authored” by the singer. Producers, who own studios, hire musicians and songwriters, who make up a song title that is usually based on a catchy phrase. The lyrics themselves are most frequently a kind of mixing up and reassembling of lyrics from a stock of phrases and lines, rooted in traditional songs whose “composer” was the rural community from which they emerged. Having chosen the songs and the arrangements, the producers then hired a singer, handed him or her the lyrics, and quickly made a recording of the voice. The bulk of the work producing the sound of the song was done by the musicians and particularly the arranger. The singer was a hired hand, who had no input into the overall sound or lyrics of the song. Once that work was done, the song was released on cassette. Production was quick, and there was a great deal of repetition. If one song or phrase caught on, it was quickly imitated by rival producers. If the songs “expressed” anything, it was the work of the producer and perhaps a skilled studio musician who did the arranging. The singer was much less important as the “author” of a song than the producers and the studio musicians, although the recording was released under his or her name and (usually) with his/her photo on the cassette.

2. Rai is “rebel music.” Its political and social significance is analagous to that of Elvis or Johnny Rotten or Bob Marley.

An exemplary quote: “At its heart, [rai is] music of the oppressed and impoverished...” (Tsioulcas, 2001)

This notion has been central to the marketing of rai in the West. The first two influential rai collections released in the US (and they are great) were called

Rai Rebels (1992) and

Rai Rebels, Volume 2 (1992). The most recent compilation from (Cheb) Khaled is:

Rebel of Rai: Early Years (see cover above).

The notion that rai is about resistance is the result of the imposition of a certain Western model. Rai in this frame is seen as a form of music that struggled against puritanical taboos rooted either in Islam or in post-revolutionary Algerian statist socialism. Rai's effect, in this interpretation, is something like Elvis shaking his hips and toppling Victorian sexual mores, or the assault on convention by the Rolling Stones or punk rockers.

Things are rather more complicated. Here are a few examples.

Rai musicians from the early period of the genre's development in Oran were typically referred to by the designation of

cheikh or

cheikha. (The sort of music they performed is usually called

melhoun.) In the case of the male cheikhs, there was nothing particularly “subversive” about them or their music. As performers of music of rural (and particularly Bedouin) origin, they were lower on the cultural hierarchy than performers of more prestigious genres of music of urban origin, particularly Andalusian. Within their milieu, however, they were respected masters of the craft (and hence the title cheikh, which implies age and experience.) The female cheikhas were not precisely the analogues of the cheikhs, however. While a “cheikh” in the rai field was a respected master, a “cheikha” was more or less synonymous with a prostitute. Cheikhas were distinguished by the fact that they performed their music before male audiences—in cafés where alcohol was served, in brothels, etc. The notion that a woman who performed music in front of males as licentious has a long history in the Middle East and North Africa, and it only began to change during the twentieth century. The issue of whether it is respectable for a woman to perform music in mixed company remains a point of tension and struggle throughout much of the region. So a rai cheikha was not so much a “rebel” as a disreputable character. It was not the lyrics she sang that made her unrespectable. The lyrics she sang may (or may not) have dealt with risqué topics like romance or alcohol, but these were not the source of her lack of respectability. Rather it was her structural position that rubbed against convention.

Were rai singers “rebels” during the Algerian war of independence? The evidence is mixed. According to Morgan, the cheikhs who sang traditional, “Bedouin” rai (or melhoun) tended to be regarded as collaborators. Cheikh Hamada (photo above), however, was an exception, a critic of the colonial administration whose son was executed by the French (Morgan 414). (

Here's a short clip of Cheikh Hamada live. You can download an exceptional example of melhoun, from Cheikh Mohamed Reliziani,

here.)

It is sometimes claimed that Cheikha Rimitti had some connection to the national liberation struggle, but I'm not sure there is any evidence of this. Check out Banning Eyre's interview with Cheikha Rimitti in 2000.

Banning: Rai music has a reputation as a music of social rebellion. Did you think of it that way back in the beginning?

Rimitti: I divide my career into three periods: the period of 78 records, the period of 45s, and the period of cassettes. Throughout all these periods, I have always sung the ordinary problems of life, social problems, yes, rebellion... Rai music has always been a music of rebellion, a music that looks ahead.

Eyre's prompting elicits the desired response, that, of course, rai was about rebellion. Note that Rimitti's answer is very general—rai is rebellious because its lyrics refer to ordinary and social problems. She says nothing about what she did during the period of the national liberation struggle, for instance. Then Rimitti goes on to the subject that she is really interested in—to complain about how rai's big stars, Khaled, Chaba Fadela, and Chaba Zahouania, have ripped off her songs without giving her any credit!On the other hand, celebrated singers of ouahrani music were connected to the Algerian revolution.

Ouahrani (or wahrani) developed in Oran in the 30s and 40s out of

hadhari music, a genre closely related to rai, which modernized under the influence of the Egyptian popular music of Muhammad Abdul Wahhab, Umm Kalthoum, and Farid al-Atrash. (Instruments changed, as did musical styles.) Ouahrani is acknowledged today as one of the sources of the pop rai that emerged in the seventies. Most notably, ouahrani star

Ahmed Wahby left Algeria to join the FLN in Tunisia in 1957. After independence, he eventually became secretary general of Algeria's National Union of Cultural Arts (Tenaille 38). According to Morgan (417), the other two main ouahrani stars, Ahmed Saber and Blaoui Houari, were also arrested by the French during the War of Independence.

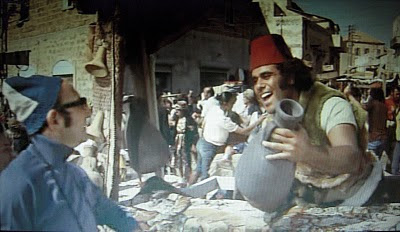

I also believe too much has been made of the “resistant” nature of the modern “pop” rai that developed beginning in the late '70s. The world music around rai is full of such claims. The fact is that rai producers in the first half of the 80s, before rai really went mainstream in Algeria, played up the more licentious and bawdy lyrics, which they handed to their singers when they entered the studio to record a number. Once rai became mainstream, the same producers actively discouraged raunchy lyrics, and instead cleaned them up in order to gain wide popular acceptance. Risqué rai sold in the first half of the decade, modest rai sold in the second half. The point was to make money, not to “resist.” Check out, for instance, Djamel Kelfaoui's highly recommended documentary,

Algérie, Memoire du Raï, which shows Khaled in concert in Oran in 1985, at the first, officially sponsored rai concert. He's wearing a tuxedo. (See Kelfaoui's doc

here--well worth watching even if your French is weak. The photo at left is "ripped" from the film.) Such an image had to be erased from the account of rai that emerged in the late eighties and early nineties in order to “sell” the music to Westerners. (Even though on that first

Rai Rebels album--see above--Khaled is also in a tux.)

Rai music did become a target of the radical Islamists of the FIS (Islamic Salvation Front) and especially the Armed Islamic Groups (GIA) during the Algerian civil war. This did not make rai especially “resistant,” either—except in the eyes of its romantic Western followers—since the genre was strongly embraced by the Algerian military government, in response to Islamist opposition. In order to articulate an image of cultural “moderation” and to appeal to youth, the repressive “pouvoir” embraced rai music.

Rai is probably the most “resistant” in the context of France, simply by virtue of the fact that it is an important expression of Arab culture, and therefore, represents a kind of threat to the extreme right and racists. On the other hand, rai is often deployed as the representative of “acceptable” Arab culture in France, as opposed to unacceptable, non-assimilating Arab culture, particularly of the orthodox Islamic variety. Arabic music, especially of the “hybrid” variety, like couscous, can often be more easily assimilated and embraced by liberal-minded “native” French people than real, living and breathing, working class Arabs demanding civil rights. The film

100% Arabica is a particularly good example of this kind of discourse. The plot revolves essentially around the struggle for power in a mostly Arab neighborhood in Paris, between Islamists (intolerant, corrupt) and rai artists (played by stars Cheb Mami and Khaled), who are fun, tolerant, and lovable, and who appeal not just to Arabs but to “native” French as well. The old good Arab/bad Arab schtick.

When the “rebellious” aspect of rai is presented, however, it's almost always rai as resistant to conservative values or Islamist extremism in Algeria. Rai is almost never presented as resistant to French values of assimilationism, intolerant secularism, and monoculturalism.

3. East meets West.What is frequently hailed about rai is that it represents—in its contemporary, “pop” version—an encounter between “Eastern” and “Western” culture. There are a whole variety of terms that are typically used to describe this sort of encounter, used in both journalistic and academic literature. Hybrid, fusion, Moroccanroll, and so on.

What I want to contest is the purported novelty of the so-called “fusion” that rai is meant to represent. It is typically presented as if the emergence of pop rai represented a kind of first-time encounter, remarkable because—at last—Middle Eastern musicians had finally decided to embrace “Western” instruments. Of course, for contemporary audiences (since the development of the world music genre) it's the fact that rai artists have variously incorporated rock, funk, reggae and hip-hop that makes the music remarkable—different, yet also familiar.

It's difficult to know where to begin a response. My response can only be partial. Of course the entire discourse depends upon the deeply rooted cultural truism, that the West and the East, Europe and the Arab World, are radically, ontologically, different and opposite. This is why East-West fusions continue to be exotic and exciting for world music fans, because the frisson generated by such “discoveries” is grounded in the notion that Euro-American and Arab cultures are inherently distinct. Rap music in the Arab world, and especially Palestine, is a new kind of novelty. (It's almost unnecessary to cite Said's

Orientalism as a source here, right?)

This discourse of course forgets the deep connections between European and Arabic music—the evolution of the guitar from the lute, which is essentially the Arab 'ud (the name lute comes from the Arabic

al-'ud) or the connections between Spanish flamenco and Arabic music, dating from the Andalusian period (

olé in Spanish comes from the Arabic word

allah or God, which is sometimes used in Arabic in much the same way as

olé).

But let's jump to the modern era. The apprehension of rai's “fusion” as novel also depends on a forgetting of the entire history of French colonialism in Algeria. I only know bits of the history of Algerian borrowings from French culture, but here are a few examples. One of my favorite, about which I know almost nothing, is this album from Buda Musique,

Algeria: Humorous Songwriters Of The 30's. It's variously American swing, French dancehall, rumba, and so on, with Arabic lyrics, and often, as Richard Gehr notes, sounding like Jimmy Durante. You can listen to samples

here.

And then there is ouahrani, one of the predecessors of modern rai. You can get a sense of how great the ouahrani artist Blaoui Houari (pictured at left) was by a look at Djamel Kelfaoui's documentary,

Algérie, Memoire du Raï,

here, at about 16 mins. As mentioned above, one of the main influences on ouahrani was Egyptian popular music which, of course, borrowed heavily from Western musical sources. Muhammad Abdel Wahab of course was more inclined to sample from Western music than the more conservative Umm Kalthoum, but all the stars of Egyptian popular music did it, and they were quite eclectic in their borrowings. One of my favorite examples is the scene from the film

Ghazal al-Banat [1949], where Abdel Wahab leads an orchestra that is playing a hoe-down, composed by him. The “Western” sources included a lot of Latin American genres, such as the tango, the rumba and (by the fifties) mambo. Check out, for instance, tangos sung by Egyptian artists like Layla Mourad or Abdel Wahab on the album,

Tango Oriental: Arabic, Turkish, Greek & Israelian Tangos from 78 rpm Recordings. (Listen to samples

here.)

One of the musicians who sometimes played on the ouahrani artists on their recordings was Maurice El Medioni, an Algerian Jew from Oran. Medioni developed his distinctive style of “pianoriental” in part under the influence of American soldiers he met during the Second World War. They brought records along with them, and the boogie-woogie piano styles and the beats of rumba were particularly important for Medioni's development. In this regard, he particularly cites the importance of Puerto Rican soldiers he met. (Medioni is still

alive and active. He was “rediscovered” in the mid-nineties, and his

four albums are easy to put your hands on. Medioni appears on Khaled's 2004 release

Ya-Rayi, along with Blaoui Houari). Medioni also recorded with a number of the remarkable Algerian Jewish musicians who performed in a musical genre known as “francarabe,” mixing Arabic and French lyrics and Eastern and Western musical styles. Among the best known were Lili Boniche,

Blonde-Blonde ,

Luc Cherki, Rene Perez, Lili Labassi, Raoul Journo, and Line Monty. Check out this song of Line Monty on

youtube (and note that the photo was taken by

me!) Or “Alger Alger” (a waltz) from

Lili Boniche, with piano by Medioni.

Rai artists, therefore, followed in the wake of decades of borrowing by Arab musicians of various musical forms and instruments from the West. And rai artists weren't even the first in Algeria to borrow rock styles. Among the Algerian bands playing rock, singing in Arabic and thereby giving the music an “Eastern” inflection, were El-Abranis, two of whose songs appear on a revelatory collection of Middle Eastern rock music from the sixties and early seventies, entitled

Waking Up Scheherezade. And you can download one El-Abranis' songs

here, from the invaluable blog Radiodiffusion Internasionaal Annexe.

There you will also find a rock recording by Rachid and Fathi (Baba Ahmed), the very psychedelia-inflected and Turkish-rock sounding

“Habit En Ich.” The brothers were in a rock band called The Vultures in the 60s, then recorded as a duo, and subsequently went on to become the most important producers of rai music. They revolutionized the business in fact because they introduced a multi-track recorder. (Rachid Baba Ahmed was assassinated by Islamists in 1995.)

What

is somewhat novel about rai is not the influence of Western music, but that rai artists, starting with Khaled, began to make recordings with the explicit aim of attracting audiences in the West. Before this, musicians borrowed from Western music with the idea of appealing to local audiences. By that time, Khaled was in the West, in France. Khaled's first effort in this regard was

Kutché (1989), his first album recorded in France—when he still went by Cheb Khaled. The real breakout, however, was the next one,

Khaled (1992) which, with production help from Don Was, and the hit single “Didi”, made him an international star. You can see, and hear, why "Didi" was such a hit,

here. Of course, an important part of his “Western” audience, in Europe at least, was made up of Arabs. And “Didi” was a global hit—throughout the Middle East, including Israel, in India, and East Asia. (Only the US, in fact, didn't embrace it—except in world music circles.)

More on rai misconceptions coming soon!

Sources:Eyre, Banning. 2000. Interview with Cheikha Rimitti. Afropop Worldwide.

http://www.afropop.org/multi/feature/ID/44/?lang=gbMazouzi, Bezza. “Rai,”

Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The Middle East, ed. Virginia Daniels et al, pp. 269-72. Garland.

Morgan, Andy. 2000. “Rai.”

Rough Guide to World Music, vol. 1, 413-422. Rough Guides.

Schade-Poulsen, Marc. 1999.

Men and Popular Music in Algeria: The Social Significance of Raï. University of Texas Press.

Sylvain, Siclier. 2002. “Khaled celebre le passé et le futur du rai,”

Le Monde, June 6.

Tenaille, Frank. 2002.

Le Raï: De la bâtardise a la reconnaissance internationale. Actes Sud.

Tsioulcas, Anastasia. 2001. “African waves: A sonic sampling from the continent: Cheb Mami.”

Down Beat 68(4):42.

Articles by me (single or jointly) (note there's a

lot of repetition).

2004. “The ‘Arab Wave’ in World Music after 9/11.”

Anthropologica 46(2)

2003. “Rai's Travels.”

MESA Bulletin 36(2):190-193.

2002. “The Post-September 11 Arab Wave in World Music.”

Middle East Report 224:44-48.

2001. “Arab ‘World Music’ in the US.”

Middle East Report 219:34-41. (Reprinted on the National Instititute for Technology and Liberal Education Arab World project website,

here)

1996. “Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Rai, Rap and Franco-Maghrebi Identity” (with Joan Gross and David McMurray). In S. Lavie and T. Swedenburg, eds.,

Displacement, Diaspora, and Geographies of Identity, pp. 119-155. Durham: Duke University Press. Reprinted in Jonathan Xavier Inda and Renato Rosaldo, eds.,

Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader, pp. 198-230. London: Blackwell Publishers, 2001.

1994. “Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Rai, Rap and Franco-Maghrebi Identity” (with Joan Gross and David McMurray).

Diaspora 3(1): 3-39. Reprinted in Inderpal Grewal and Caren Caplan, eds.,

An Introduction to Women’s Studies: Gender in a Transnational World, pp. 471-475. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001. (first edition)

1992. “Rai, Rap and Ramadan Nights: Franco-Maghrebi Cultural Identities” (with Joan Gross and David McMurray).

Middle East Report 22(5) 11-16. Revised version in Joel Beinin and Joe Stork, eds.,

Political Islams. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1996.

1991. “Rai Tide Rising” (with David McMurray).

Middle East Report 21(2): 39-42

Chuck Willis is one of the most celebrated of the R&B turban wearers, and was known as the "Sheik of the Blues." I can't authenticate Moore's claim. Willis was from Atlanta, but perhaps he met up with Moore in Cleveland. Willis had his first hit in 1952; Moore was in the army from 1950-53. When did Willis start wearing the turban? Dunno.

Chuck Willis is one of the most celebrated of the R&B turban wearers, and was known as the "Sheik of the Blues." I can't authenticate Moore's claim. Willis was from Atlanta, but perhaps he met up with Moore in Cleveland. Willis had his first hit in 1952; Moore was in the army from 1950-53. When did Willis start wearing the turban? Dunno. Moore barnstormed as Prince DuMarr until 1950, when he was drafted. In the mid-1950s, Moore moved for a time to Seattle, and took up the "Prince DuMarr" role again in a review headlined by sax player Big Jay McNeely. Presumably, again in turban. Perhaps it was in the Seattle period that Chuck Willis saw him in turban. This photo too is of Moore as "Prince DuMarr"--a poor reproduction from the LP cover of Hully Gully Fever.

Moore barnstormed as Prince DuMarr until 1950, when he was drafted. In the mid-1950s, Moore moved for a time to Seattle, and took up the "Prince DuMarr" role again in a review headlined by sax player Big Jay McNeely. Presumably, again in turban. Perhaps it was in the Seattle period that Chuck Willis saw him in turban. This photo too is of Moore as "Prince DuMarr"--a poor reproduction from the LP cover of Hully Gully Fever. And here are a few more turban images. It appears that Norton Records is really into the turban aesthetic. Here's the cover of Turban Renewal, a tribute album to Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs record. (Sam is another famous turban wearer.)

And here are a few more turban images. It appears that Norton Records is really into the turban aesthetic. Here's the cover of Turban Renewal, a tribute album to Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs record. (Sam is another famous turban wearer.) And the cover for another Norton release, Hannibalism!, from R&B singer The Mighty Hannibal.

And the cover for another Norton release, Hannibalism!, from R&B singer The Mighty Hannibal. This is the cover of Norton's 2009 catalog. Unfortunately I can't find a better reproduction. Note that it features turbaned artists like Rudy Moore, Sam the Sham, Hannibal, Screamin' Jay Hawkins and The Egyptians, and that it advertises "Turban Contemporary Music."

This is the cover of Norton's 2009 catalog. Unfortunately I can't find a better reproduction. Note that it features turbaned artists like Rudy Moore, Sam the Sham, Hannibal, Screamin' Jay Hawkins and The Egyptians, and that it advertises "Turban Contemporary Music." Still more. Two LP covers from be-turbaned Hammond B3 ace Lonnie Smith: Afrodesia (1975) and Funk Reaction (1977).

Still more. Two LP covers from be-turbaned Hammond B3 ace Lonnie Smith: Afrodesia (1975) and Funk Reaction (1977).

Finally, another from King Khan, who is truly keeping "turban contemporary" alive.

Finally, another from King Khan, who is truly keeping "turban contemporary" alive. The new album of King Khan and the Shrines, Invisible Girl, is terrific. And turbanated.

The new album of King Khan and the Shrines, Invisible Girl, is terrific. And turbanated. Ok, one more. This is the last, and from a different turban context and aesthetic. Kate Moss, May 2009.

Ok, one more. This is the last, and from a different turban context and aesthetic. Kate Moss, May 2009.

There are other outfits whose referents are less clear to me. Rihanna plays poker with the guys in this one. And she wins. Because she's hard. "And my runway looks so clear," she sings. "But the hottest bitch in heels right here."

There are other outfits whose referents are less clear to me. Rihanna plays poker with the guys in this one. And she wins. Because she's hard. "And my runway looks so clear," she sings. "But the hottest bitch in heels right here."