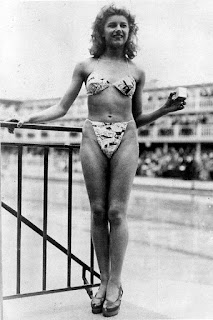

Sayed Darwish (picture courtesy of the Friends of Sayyid Darwish Association; found here)

From a

report in Egypt Independent on yesterday's massive demonstration at Tahrir.

A lonely island in a sea of Salafis, the National Coalition for Change stage boasts a handful of people, mostly in their early twenties. "We all remember Sayed Darwish and his beautiful lyrics," one youth bleats into the onstage microphone to a scattering of an audience (many of whom are wearing Abu Ismail badges and pins). "Here's one of his most beautiful songs, which we all know and love. It's called 'So It Goes.'" The youth begins to sing, but his voice is easily drowned out by the pro-Hazem stages on both sides. The small crowd disintegrates.

I am guessing that the song in question by Sayed Darwish is "Aho Da Lli Saar." On the run-up to the anniversary of the overthrow of Mubarak, the BBC produced a radio

program by Reem Kelani, in which she explores the music of the revolution and in particular, the importance of Egyptian composer and singer Sayed Darwish in it. I

posted about the program on the Merip blog, but I did not discuss what was said about "Aho Da Lli Saar." Given what happened yesterday, it is useful to go back to Kilani's program.

She opens by introducing Khaled Abu Naga, who co-produced and starred in the acclaimed 2010 film

Microphone, about the underground art scene in Alexandria. Although the film was produced before the outbreak of the revolution, it in many ways seems to anticipate it, in its depiction of a vibrant artistic scene that is frustrated in its efforts to develop and put on its work (particularly the music) in public. Frustrated both by the bureaucratic agencies of the state, backed up by the security forces, and by the Islamist forces. (If you've seen the film, then what occurred yesterday feels like a cruel throwback.) The animators of the scene depicted in the film are the same educated, enthusiastic, creative youth segment of Egypt's urban population who did much of the demonstrating and fighting at Tahrir in late January and early February in 2011. And it is well-known that one of the positive effects of the revolution was both to release all kinds of creative and artistic energies, as well as bring into public view artistic movements and tendencies that had been repressed and marginalized under the Mubarak tenure. No wonder, then, that many, as Reem Kelani observes, regard

Microphone as the film of the revolution.

Khaled Abu Naga tells Kelani that it was Said Darwish who the youth in Alexandria went back to, fo find lyrics that depicted the situation they were living in in early 2011, in the days of the revolution. And the song that

really depicted how they all felt, he says, was "Aho Da Lli Saar," which Kelani translates as "This Is Where We're At." The song dates from the 1919 Revolution, which erupted in part due to the frustrations of Egyptians who felt that their active participation in the First World War (around a one and a half million Egyptians were conscripted into the Labor Corps) should have earned them independence from Britain.

Kelani provides a translation of some of the lyrics of the song (written, in fact, by Badi' Khayri; Darwish wrote the music):

Egypt, O mother of wonders

Your people are great and your faults are not

Watch out for those who love you

For they are the champions of your cause

In the background, we hear the Darwish song, performed by the Alexandrian group, Massar Egbari ("Compulsory Detour"), who are also appear in the film

Microphone.

I happened to see

Karim Nagi perform at Georgetown last Wednesday evening, and one of the numbers he did was "Aho Da Lli Saar," which he translated as "This is what happened." Nagi is a fabulous dancer and a multi-talented percussionist and buzuq player. He is the animating force behind

Turbo Tabla, whose two albums I highly recommend. He is also a great lecturer -- if you are looking for someone to provide an excellent introduction to Arabic music, be sure to hire Karim.

But I particularly loved Karim's performance of Sayed Darwish's "Salma Ya Salma" and "Aho Da Lli Saar." Before singing them he translated both songs into English -- and I regret not recording these. In his program notes, at least, Nagi provided a translation of a few more lines of "Aho Da Lli Saar":

This is what happened, you cannot blame us

The wealth of our country is beyond our reach

Let us not fight nor envy

Unite our hands, and be strong for the cause

Here are some more versions of the song:

Ali Haggar's -- which predates Massar Egbari's, and on whom Massar Egbari's version seems modelled.

Fairuz does a version too. (I'm pretty sure this is from her

Live at Beiteddine 2000 album, the title transliterated as "Ahoua dalli sar.")

An amazing

performance of the song, from January 10, 2011 (two weeks before the start of the revolution), done at Al Sawy in Cairo by members of the cast of Microphone, "In solidarity with the victims of terror in Alexandria." In reference, clearly, to the

terror bombing of a Coptic church in Alexandria on December 31, 2010, that killed 21 and wounded at least 96. Many blamed the bombing on the regime.

Fairuz's celebrated son Ziad Rahbani also has a

version, very similar to his mother's. Apparently recorded in Damascus in 2008.

There are other versions as well, but it would seem that Ali Haggar, Fairuz and Ziad Rahbani in particular have played an important role in keeping the song alive in Arab popular memory.

Unfortunately, I cannot find a version of Darwish's version on youtube -- I assume there are downloads available, probably of dubious legality.

Here are the Arabic lyrics, with a transliteration and a translation into English, which I found

here. I've changed a couple things. There are some discrepancies between what is below and the translations I've posted above, so if someone wants to help out and fix these, and provide some more commentary that would be terrific.

اهو دا اللي صار, و ادي اللي كان

aho dalli sar w dalli kan

this is what happened, this is what was!

مالكش حق

malaksh 7a2

you don't have the right

ملكش حق تلوم عليا

malaksh 7a2 tloom 3alayya

you don't have the right to blame me

تلوم عليا ازاي يا سيدنا

tloom 3alayya ezay ya sayedna

how can you blame me sir ?

و خير بلدنا مهوش في ادنا

w 5air beladna mahoosh fe edna

and the wealth of our country is not in our hand

قولي عن اشياء تفدنا

2olli 3an ashya2 tefedna

tell me about things that help us

بعدها بقى لوم عليا

ba3daha ba2a loom 3alayya

then you can blame me

مصر يا ام العجايب

masr ya 2om el 3agayeb

Egypt, the mother of wonders

شعبك اصيل و الخصل عايب

sha3bik aseel wel 5sl 3ayeb

your people are noble, your faults are not

خلي بالك مالحبايب

5alli balik mel 7abayeb

take care of your loved ones

دول انصار القضيه

dool ansar el 2adeya

those are the supporters of the matter

بدال ما يشمت فينا حاسد

bdal ma yeshmat feena 7asid

instead of the gloating of jealous people

ايدك في ايدي نقوم نجاهد

edak fe edi n2oom negahid

let's hold hands and fight

احنا نبقى الكل واحد

e7na neb2ael kol wa7id

we all become one

والايادي تكون قويه

wel 2ayadi tkoon aweya

and hands become strong

(Footnote 1: While working on this post I found this

blogpost that accompanies Reem Kelani's BBC piece. It is an invaluable resource about the significance of Sayed Darwish and about the music that was performed on and played on and around Tahrir during the days of the revolution. Please have a look.)

(Footnote 2: on the treatment of Egyptians in the British army: the noted novelist E.M. Forster lived in Alexandria during the First World War. He took up with an Egyptian tram conductor named Muhammad al-Adl, who became the love of Forster's life. In an attempt to improve his position within the government bureaucracy, Forster was able to help Mohammad get a job with the British military on the Suez Canal, where he did low-level intelligence work. Al-Adl described himself as a "spy." Muhammad eventually came down with a fever, received miserable treatment in the badly run hospital and nearly died. Upon his recovery, he used to let Forster know that his British military employers treated him like "dirt," as they treated all Egyptians. Muhammad was arrested and sentenced to six months in hard labor, after an incident in which he and a friend encountered some Australian soldiers in Mansourah, who offered to sell them a revolver. Muhammad considered himself innocent, but he was humiliated, bullied, and badly fed in prison. Muhammad, whose health was impaired by both his time spent in a horribly run British military hospital and in prison, died of consumption in November 1922.

It seems that Forster's knowledge of the evils of colonialism and the bad treatment meted out to Egyptians during the war, mostly via Muhammad, motivated him to write a historical summary for a pamphlet, called

The Government of Egypt, put out by the Labour Research Department in summer 1920. Forster did not go so far as to argue for Egyptian independence, but for Egypt to be put under a League of Nations-sponsored mandate. It appears as well that Forster's relations with Muhammad had a great deal to do with the critiques of colonialism that are expressed in his famous novel

Passage to India. Forster used to put on Muhammad's ring every day, a ring that Muhammad had willed to him, and when he finished the last lines of Passage to India, Forster put down his pen and picked up a pencil that had belonged to Muhammad and wrote in his diary that he had finished the book.

All this, I learned from Michael Haag's

Alexandria: City of Memory, Yale University Press, 2004.)